Whose Myth?

The echo and the diaspora

Lucreccia Gomez Quintanilla

(Master of Fine Arts)

A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at

Monash University in 2021

MADA

Copyright notice

© Lucreccia Gomez Quintanilla (2021).

I certify that I have made all reasonable efforts to secure copyright permissions for third-party content included in this thesis and have not knowingly added copyright content to my work without the owner's permission.

Abstract

This research examines the intertwined relationship between sound and the communication of knowledge. It does so by focusing on the echo as a metaphor, a methodology, a cultural artefact and an aesthetic effect within the artistic context. In this manuscript, the echo works as an artistic and theoretical device to engage within multiplicity, with Latin American diasporic narratives within a variety of cultural manifestations. The research presents a case for the relational.

An artistic led project, the creative works push the possibilities of the echo, a sound into the visual and the sculptural. Although it is important to note from the outset that my engagement with sound, a medium I have concentrated on, is grounded within Central American popular music. My extended family played and taught music professionally and even though I, for various reasons beyond my control, did not learn to play an instrument in this same way, this is the foundation that forms my understanding of sound. My engagement with music has been through DJing, taking music from here and there and blending it together using equipment such as decks, records, digital files and laptops. Accordingly, this research reveals the need practice ways of engaging with culture in ways that are generative, and aggregative.

With specific consideration of the nature of the echo as an effect, a metaphor and an artistic and theoretical device to engage with narratives in their multiplicity. The research presents a case for understanding the sound within the oral tradition as a way to articulate the complex.

This research recognise the importance of acknowledging specificity, and contributes to the questioning of long-held unchallenged understandings of non-Western sounds. At the same time, this research highlights the importance of an interrelational approach that is grounded in a need to work collaboratively to create space and language in which to generate, aggregate and amplify knowledge.

Declaration

This declaration is to be included in a standard thesis. Students should reproduce this section in their thesis verbatim.

This thesis is an original work of my research and contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at any university or equivalent institution and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text of the thesis.

Print Name: Lucreccia Quintanilla

Date: 5/3/2021

Publications during enrolment

Solo Exhibitions

2019 A Ripple and an Echo, Linden Contemporary.

2017 A Steady Backbeat TCB Inc. Melbourne.

Group Exhibitions

2020

WestSpace Offsite Series Curated by Tamsen Hopkinson

Speaking Surfaces, St Paul’s gallery, Aukland University of Technology Curated by Charlotte Huddleston.

Fluidity, Incinerator Gallery, Curated by Jake Tracey.

res[on]ance [off] Curated by Gabrielle White, Brisbane QLD

2019

Bundoora Homestead Arts Prize exhibition

M_othering the perceptual ars poetica, curated by Abbra Kotlarczyk and Antonia Selbach, Counihan Gallery, Melbourne

A World of One’s Own, Ballarat Regional Gallery,Curated by Tai Snaith

Shapeshifters, New Forms of Curatorial Research commissioned artist. Curated by Tara Mc Dowell. MADA Gallery

A Night in Hell, performance even at Seventh Gallery, curated by Mel Deerson

2018

Session Vessels, AirSpace, Sydney, Curated by Raffaella Pandolfini

Family Grimoires, Seventh Gallery Melbourne, Curated by Diego Ramirez.

We, Bundoora Homestead curated by Renee Cosgrave.

XYL, Curated by Sisters Akousmatica, MONA FOMA, Tasmania.

2017

Everything Spring, curated by Julia Murphy, The Honeymoon Suite Melbourne.

Mountain Dew, Banff Centre for Creativity, Canada

Collaborative and out of gallery projects

2021

Makeshift Publics, Artshouse, Melbourne.

2019

Live and soundsystem collaboration with Sarah Crowest Magdalene Laundry, Abbotsford Convent, Melbourne.

Live sound collaboration with Galambo (Bryan Phillips) as part of Polyphonic Social, Liquid Architecture supporting Chino Amobi and Nina Buchanan. Magdalene Abbotsford Convent.

Perspective Block Party - Closing of the Getrude Street Projection Festival - Soundsystem operator - Other Planes of here Soundsystem

J’Ouvert, sound designer, collaboration with Makeda Zucco, Dark MOFO, Tasmania

Mi Gente soundsystem party, MPavillion - Soundsystem operator - Other Planes of here Soundsystem

2018

Barrio//Baryo Next Wave Festival, in collaboration with Caroline Garcia, artist, curator, stage designer, DJ, Soundsystem operator - Other Planes of here Soundsystem

Precog Curated by Sarah Scott, The Tote Hotel.

Respondent to the work of Abhishek Hazra, Draghima Dithyrambic curated by

Kelly Fiedler and Westspace Inc.

Departed Acts, Curated by Made Spencer, MPavillion, Melbourne

2017

Radio art piece for Radia FM International Radio Art Network - curated by Sally Ann McIntyre.

Published writing

2020

Essay in response to finalist artist Brian Fuata’s practice for the Anti Live Art Prize, Filand

2019

Famili Launch review for Djed Press

Records of Displacement and the Echo as a Beckoning Artefact with Fjorn Butler. Disclaimer Journal.

2018

UN Magazine review of Selina Thompson's Salt

Collaborative piece with Léuli Eshraghi republished in Absolute Humidity - edited by Tess Mauder

2017

UN Magazine review of Nastio Mosquito's performance work Respectable Thief

Awards and residencies

2019

Bundoora Homestead Arts prize finalist

2017

One month funded residency BAIR Spring Intensive, The Banff Centre for Creativity, Canada.

Bibliography

2019

Briony Downes, Artguide, Lucreccia Quintanilla: A Ripple and an Echo, Exhibition preview

2018

Interview by Fjorn Butler, The Minority Report, http://min.report/records-of-displacement-lucreccia-quintanilla/

2017

Diego Ramirez, 'Lucreccia Quintanilla: The Void After The Colonies', http://www.dumb-brunette.com/lucreccia

Presentations

Writing and concepts presentation

Speaker at Sounds In The City Conference organised by Sound System Outernational (Goldsmiths University), Universita L’Orientale Napoli, Italy.

2018

Moderator for Melbourne Writers Festival Panel: Resistance and Lyricism

Moderator for discussion with sound Artist Klein in conversation with Ripley Kahara and Makeda Zucco,

2017

Art, Agency, Action panel speaker for the National Association of Visual Arts.

Moderator of discussion and event for Hannah Catherine Jones: Afrofuturism an Gesamtkunstwerk a performative lecture alongside a presentation by artist Atong Atem. Part of Liquid Architecture and Cyclops joint project.

Music mixes as DJ General Feelings

2021

Point Blank Label Mix

https://soundcloud.com/pointblankaus/pbg-mixes-008-general-feelings/likes

2020

https://soundcloud.com/cloudcover_fm/cc040-dj-general-feelings

A series of Mixes commissioned by 3Ply Publishing

Mix for Cool, Calm and Collected Series

2018

Women of Reggaeton mix for TSV label

I hereby declare that this thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at any university or equivalent institution and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text of the thesis.

This thesis includes one original submitted publication. The core theme of the thesis in this publication is opacity in the work of artist Brian Fuata. The ideas, development and writing up of this paper in this thesis were the principal responsibility of myself, the student, working within the Doctorate of Philosophy under the supervision of Marian Crawford.

In the case of chapter 2 my contribution to the work involved the following:

The re-edit essay in response to finalist artist Brian Fuata’s practice for the Anti Live Art Prize, Finland

I hereby certify that the above declaration correctly reflects the nature and extent of the student’s and co-authors’ contributions to this work. In instances where I am not the responsible author I have consulted with the responsible author to agree on the respective contributions of the authors.

Student name: Lucreccia Gomez Quintanilla

Date: 5/3/2021

Main supervisor name: Marian Crawford

Date: 7/3/2021

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my supervisors, Marian Crawford, Michelle Antoinette, Helen Johnson, and Helen Hughes. Milestone panel members who have given me much support and read my work and provided invaluable feedback: Fiona Mc Donald, Nicholas Mangan and Jan Bryant. Peers Brian Fuata, Fjorn Butler, Rebecca Hobbs, Sarita Galvez, Amit Charan, Samira Farah, Del Lumanta, Megan Cope,Tamsen Hopkinson, Diego Ramirez and James Nguyen with whom I have had shared very important and invaluable and crucial conversations. Creative collaborators Bryan Phillips, Caroline Garcia. Curators Fayen D’evie and Charlotte Huddleston. For reading of drafts Sara Daly. Editor Sarah Gory for editing services rendered. For web design Kiah Reading. Edwina Stevens for soundsystem technical support and instruction. Jeff Neale fo sculptural technical advice. Charlie Sofo, Caroline Anderson and Debris Facility for support during the time of writing. My son, Ruben Heller-Quintanilla for motivating a large portion of this creative research.

This work was created in the unceded lands of the Wurundgeri people of the Kulin nation.

This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship.

Introduction

This research takes place via a variety of approaches to art and culture making, which include sound works, field recordings, music event organising and curating, DJing, sculpture, live sound performances, remixing and writing. It has been shaped by conversations, reading groups and engaging with the works of others as part of an intersectional network of artists working in Naarm, Melbourne, as well as with peers around the world. The later stages of this research have also been developed within a larger context of COVID-19. The later works produced have developed in adaptation to the conditions created by lockdowns and machine mediated relationality.

This research has thrived in what poet, writer and theorist Édouard Glissant describes as the unforeseeable meanderings of relation.1. Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press,, 1997).21. These meanderings began when my family left El Salvador, a country in Central America which has suffered much violence through colonisation and a bloody civil war and its aftermath. It is estimated that more than 25 percent of its population dispersed and migrated during the country's civil war, which began in 1979 and ended in 1992. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/el-salvador-despite-end-civil-war-emigration-continues Accessed: 7/3/2021

My approach to this contribution is based on the anecdote, the conversation, the lived experience and the exchange as it relates to both cultural and formal concerns of how the diaspora develops a voice in its multiplicity.

The echo

From the beginning of this research, the echo as a sound phenomenon was identified as the very core of the project. In the context of this research, the echo is understood as a metaphor, a formal device, an explorative device and a method of research in itself. The echo effect works as follows:

A sound is emitted by a source into a resonant space, for example a cave, an empty room or a vessel. The sound waves then bounce of the walls or surfaces and are heard again and again, depending on the length of the initial signal. The sound that is heard is called an echo. The echo becomes a rhythmic repetition as it fills the space where the initial utterance takes place. After a while, the echo’s volume dissipates into infinity. The echo occurs in strong relationality with both the first utterance and the conditions in which it manifests. Which is to say, the manifestation of the echo is directly related to a signal uttered into a resonant space but is changed as it becomes responsive to its context.

I have applied this definition of the workings of the echo to a methodological approach. The following is a list focused on intersubjectivity—that is, the sharing of ideas with the people, place and spaces that I occupy and create work within. This list has been crucial to drawing links between conceptual and aesthetic constraints in order to explore their material and aesthetic possibilities. The contours, much like the walls from which the echo bounces, that delineate this research have become a generative space of artistic research.

By presenting you, the reader, with these points I expect that you too will be able to keep them in mind as you read through each chapter.

I am operating and speaking from within a Western cultural framework. As a migrant to Australia and before that the USA, I have needed to talk myself into believing that I too to deserve to occupy this space.

There are better ways to exist on the land that I work from than the options provided by a dominant Anglo-colonial settler population.

I am trying to understand that, as a migrant, I bring new colonial attitudes into this equation.

To understand my practice is to become comfortable with the multiplicities I inhabit and embody, multiplicities that exist outside of colonial ‘mestizaje’ discourse, which is centred around categorisations of race and miscegenation.

Respect towards the experience and knowledge of First Nations People who never ceded their sovereignty and whose land I inhabit must be acknowledged at all times.

This project is to honour the experience of those who face similar complex conditions of place and diaspora.

Relationality—that is, the multiple ways of conversing such as awareness, perception and responsiveness between one and others—and intersubjectivity and the transcultural are at the core of this project.

Colonialism relies on control of the autonomy of the collective and the self. To this end, it categorises by race and allocates privilege according to this hierarchy. This project is not based around the politics of categorisation or identification with a nation state or allegiance to a flag. Nor does it defer to essentialist notions of reduced identities as performance. It does, however, acknowledge adaptable cultural genealogies and ancestral languages. This research aligns itself with Glissant’s definition of errantry, a way of defining the self as existing within a set of relations rather than as a static identity.Ibid.

Tortilla

Negotiating a space of understanding together is crucial to this research. While I was thinking of how I could explain this concept, I remembered a particularly frustrating moment in which I wanted to share something but its reception became problematised by my interlocutor’s preconceptions. This is what I like to call the tortilla incident. This was not an isolated event but a frequent occurrence, which almost always went like this:

I would introduce an Anglo-Australian friend of mine to a new food. He would respond with, for example, “This is like a pancake except made out of corn but flat and savoury.” It was a tortilla.

There seemed to be a perpetual need on my friend’s part to always centre his experience as the basis for judgement. If what I was sharing was a fruit, for example, this fruit could not be a fruit on its own nuanced terms.

It is of course natural to seek to ground one’s understanding of the world in a familiar cultural experience—as in the tortilla anecdote. What I am instead asking is that you, the reader, become what Gayatri Spivak terms “inter-literary” rather than “comparative” in approaching this text.G.C. Spivak, An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization (Harvard University Press, 2012).52. This approach applies most specifically to the experiential anecdotes present throughout this paper. They exist there to anchor a set of concerns within everyday experience and contextualise the theory in practice.

Assimilation

Another example of these lived instances involved me listening to Latin music in my loungeroom at time when I was beginning to engage more deeply with sound in an artistic context. I described to the other person in the room how this music spoke to me in a particular way. Emotionally of course, and aesthetically most certainly. My visitor proceeded to argue that my liking of this music was exclusionary. After all, he argued, music should able to be understood by everyone. Following this logic founded in a universalising Western standard, which he argued I was irrationally challenging, my engagement with Latin music was of no real substance nor relevance.

If the words of this proponent of the Western as universal— that is, a music everyone understood—were to be taken seriously, it seemed I had been given a binary to work within. In this binary, I identified two potential options to speak to my interest in this particular sound. One was to understand that the legacy of my ancestors had no space in Australia, the place I sought refuge in, and so this legacy was now irrelevant. The other acceptable logical approach would be to look at this legacy with an anthropological remove via this Western lens I had been not so generously offered —as a type of othered curiosity, in the way perhaps of World Music. Which is to say, in our conversation I was forced to take a position of ‘objectivity’ in order to engage. Neither of these options worked for me.

I had been very suspicious of the motives of assimilation from the initial stages of settling in Australia, with the intuition that erasing knowledges is a violent act, and I was beginning to become confident with my own standpoint despite having lived with the persistent Australian narrative of assimilation for some time I also felt there had to be another way other than what I had experienced as the conditional permission to perform the more acceptable stereotypes that multiculturalism presented as an option.

Cultural assimilation is a term that may be perceived by its proponents as a way to achieve a type of social cohesion rather than what is: a colonial impulse to eradicate, police and control that which is not of the coloniser/dominant cultural language. It is an essential aspect of settling into a colonised land, if you will. Therefore, to want to oppose assimilation is to open a space of complete discomfort and, if you are a migrant, this is also a dangerous space and a potentially ungrateful space. The question became of how to deal with the effects of assimilation on the self in a way that was productive for the collective.

Latent lullaby

The time of no sleep during early motherhood is one of short circuits. It is a time when one tries to avoid panic in the face of an inconsolable baby by doing the most instinctual of things. On one of these occasions I stunned myself as I sang:

Dormite mi niño

cabeza de ayote

si no te dormís

te come el coyote

The first songs I thought of singing to my child were not English-language songs about tiny spiders climbing up waterspouts, nor about twinkling little stars. They were songs I had heard before, over and over, songs I had sung to my little cousins to soothe them. Cultural defiance had struck in the most subtle, practical and unexpected of ways. Down the street, decades since I had sung the melody, there it was. Calming my child, the tears stopped running down his face and began to pour out of my eyes instead. These were Nahuatl words—ayote, meaning pumpkin, coyote—voiced again, but this time in Australia. This was not a performance work, it was an echo, an actual event, not its representation. Not that my child would have cared for the context in which the lullaby was delivered—he fell asleep as I sang.

I relate this personal story within this academic context as a way to instigate a reimagining through an artistic context. But also, it is not a stretch of the imagination to contextualise this anecdote as an involuntary trespass, a spillage of sorts against strong assimilationist expectations of conforming. I was exhausted. I thought I was doing well living a covert life and doing what assimilation asked of me. Singing this lullaby had somewhat ruptured civility as I had lived it so far. The surfacing of this lullaby was a very significant moment.

Aurality

I grew up around the making, performing and teaching of music, a legacy that I aggregate to as an artist who very often works with sounds. My works often begin with anecdotes involving personal histories, which are placed to the same importance as academic texts because they are crucial knowledge to my practice as an artist.

When speaking about Jamaican music sound and writer Louis Chude-Sokei argues that through the technology of the sound system, Jamaican sound becomes a form of collective orality:

… to study the aesthetic and material properties of (black) sound production is to study orality, migration, myth and cultural memory … [and in this way] to experience the collective sound is to become part of it.L. Chude-Sokei, Dr. Satan's Echo Chamber: Reggae, Technology and the Diaspora Process (Reggae Studies Unit, Institute of Caribbean Studies, 1997).50.

This research learns from the specificity of writers such as Chude-Sokei and applies these approaches to my own practice and that artistic material important to this research project. This research has sought to work with complexity, depth and irresolute nature of mythologies and genealogies as ongoing and grasping, an approach that works outside of the conclusion-making standards of external observation. In doing so, this research maps out how I am contributing directly to these genealogies in a respectful, adaptive and critical way.

This thesis is composed of three main chapters, which detail the implications of different facets of the echo and its use within artistic practice and thought.

The first chapter is titled The echo and its diffractions. It examines the echo within creative works completed and exhibited throughout the duration of this project. In addition, an event is documented that took place early within the research. Each of the works examined has a different approach to looking at a multiplicity of timelines, and each engages with conversations around both the intimate and collective experience of sound. The politics of relationality, experimentation and joy around the sound event is discussed in relation to the creative work of the diaspora. The work of the diaspora is placed within the context of diffraction as the action which creates the echoic effect. The chapter is indebted to the scholarship of diaspora writers whose work examines Jamaican music—reggae, dancehall and dub such as Julian Henriques and Louis Chude Sokei. My research overlays this existing research over an understanding of the echo within the echo of Mayan architecture and European lore, based on the sound within the conch shell.

The second chapter titled Ongoing narratives reconfigures ways in which the echo can be understood in human history. Further to this, it looks to mythology and science fiction as ways to frame the echo as a narrative device. The echo is examined for its capacity to think through working methods for collaboration via intersubjective and relational approaches to artmaking. This chapter takes the echo as a narrative and adaptive pragmatic force and investigates it through science fiction and anecdotes. Through this analysis of the echo, a central creative work developed within this project, a work that examines the development and physical rendering of a musical instrument from anecdote.

The third chapter titled Reverberance, Resonance and Looping engages with ideas around orality, mythology, voice and feminism through the anecdotal, Mesoamerican mythology and feminist scholar Gloria Anzaldúa’s important work into how the Latin American diaspora can find new possibilities and ways to interact within the diasporic setting. This chapter looks at the echo within the framework of a collaborative and live performance that focused on the aggregation of mythologies via sound. This part of the research makes connections between techniques in DJing and sonification and oral and written narrative forms. Crucially, this chapter considers the utterance of an echo as being a direct reflection of the conditions and surfaces which produce it.

The concluding chapter is a summary of the findings and developments from this creative research project. Further to this, it outlines the contribution of the research within the field of sound. The conclusion determines the impact and significance of this echo-led research on understandings of the intersubjective and the relational within sound. This chapter maps out the lessons and limitations within the research, and projects strategies for moving forward with future creative works based on developing a strong non-colonial-led contribution to the wider cultural landscape. This conclusion also offers insight and direction for intersubjective, relationally-focused study approaches for artists living in the diaspora.

The pull towards the sound of the echo as a metaphor and as a practical approach to cultural production resides in its ability to speak of an irreducible space, even if only for a period of time, that does not hold a physical entity beyond the human psyche. What this creative project finds in sound and specifically the echo is the presence of both the intimate and the collective, the socio-cultural, the mythological, the formal and the generative potential of working within the diaspora as an experimental site. This condition is both a privilege and a point of tension and it is here that the politics of this project resides.

Chapter 1

The Echo And Its Diffractions

Introduction

In what follows I examine the echo from different vantage points. These various ways of engaging with the echo range from the anecdotal and the archaeoacoustical through to satellite technology, dub music, soundsystem culture, and via my own creative research works.

The echo presents a grounding for entering into conversations around relationality, the adaptive qualities of knowledges that are passed down from one generation to the other, and the way the diaspora moves through its new surroundings. That said, this project is not a tragic variation of the search for identity after colonisation, with its fixation on a purity or an essential pre-colonisation identity Édouard Glissant is a poet, philosopher and critic whose influential work speaks to culture and race, and is of great influence on the Créolité movement in the Caribbean. Glissant’s work is known for its nuanced, poetic and pertinent analysis of the potential for creative acts—specifically in literature—for the diaspora and the colonised. Glissant. 17..

In particular, Glissant’s theorisation of ‘opacity’ permeates this research project. Every paragraph in this text exploring an understanding of the function of the echo in diaspora can be understood as a way to converse with ancestral knowledge while simultaneously developing ways to engage with new contexts. Opacity for Glissant, within an artwork, may work in either of two ways: as an ethical stance and as a poetics. Specifically, Glissant argues that there are wider artistic uses for an,

irreducible opacity of the text, even when it is a matter of the most harmless sonnet, and the always evolving opacity of the author or a reader.Ibid. 115

By irreducible opacity Glissant refers to an opening up to the idea that both in tactic and aesthetic approaches, an experience of what is understood as difference cannot and does not need be reduced to a single identifiable and easily categorised and reduced representation. This is important, as while acknowledging the conditions and context in which texts (or artworks) are produced, it is a main intention of this research to bypass interaction with the binary or dualistic thinking that has dominated perceptions of the world by way of Western colonisation, especially oppositionality’s of the human and subhuman based on race and culture. Following Glissant, opacity as an approach acknowledges the complexity and multiplicity of experience.

Finding through the echo

Sound as a medium, while being capable of containing cultural specificities through motifs—in much the same way as the visual—is also time-based and as such it is able to connote and conjure time-specific place and emotion. The echo in sound in particular has qualities which have historically lent themselves to being used as metaphors.

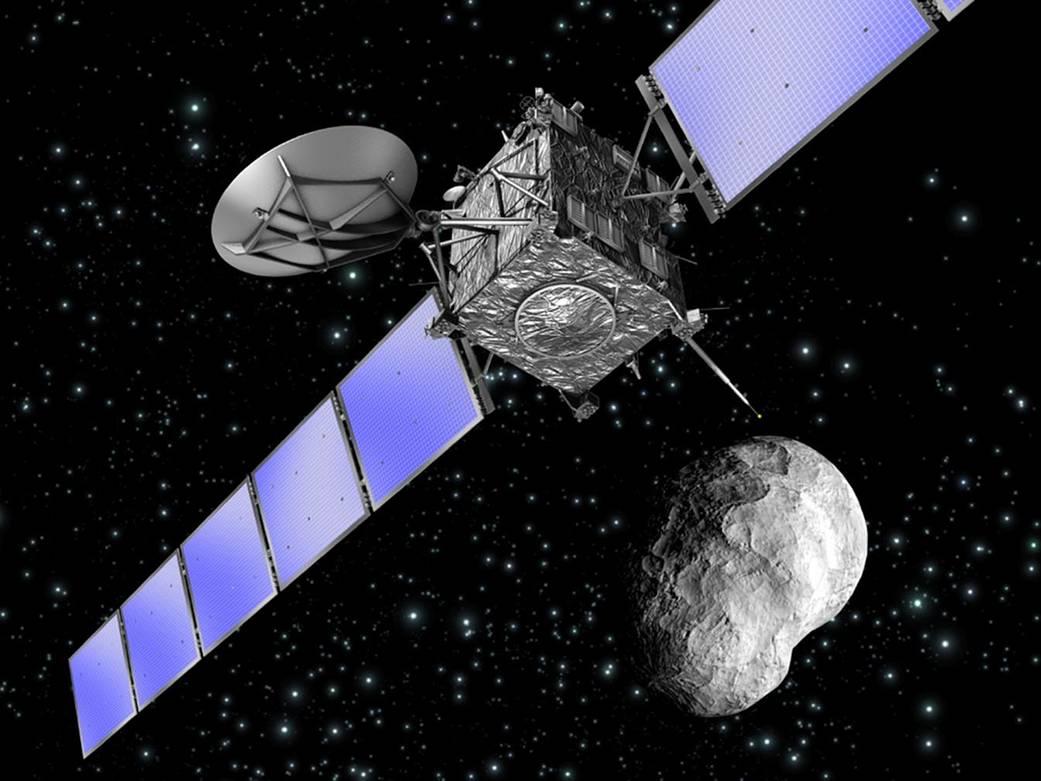

Figure 1. NASA, Rosetta space probe, 2014https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/heo/scan/services/missions/universe/Rosetta.html accessed 7/3/2021

As a sound phenomenon, the echo maintains a connection with an original sonic signal. If you imagine saying ‘hello’ within a cave for example, your word will travel and then bounce from the surfaces of the wall and so the sound you hear is both your voice as well as the greeting returned. That echo is the product of a process of refraction; the ‘hello’ is returned to you via an effect resulting from its bouncing from the walls of the reverberant space, in this instance the cave. The echo heard may have been created by the initial sound, but it is also an entity in itself.

The experimental jazz musician, poet and filmmaker Sun Ra sang ‘space is the place’ as the main verse of the song of the same title. Sun Ra, who was working at the height of the Civil Rights Movement of the late 1960s in the USA, conceived an ambitious project that looked to outer space as a site for mapping a better way of existing for African American people. The aim was to engage with its history and, in doing so, imagine radical possibilities outside of the constraints and limitations resulting from ongoing categorisations of what is considered human and non-human.

Sun Ra’s way of thinking through sound resonated with me and is important to this project, although of course I live within a vastly different personal and racial narrative to Ra. Much like the role that space played in Ra’s artistic and emancipatory imaginary, the echo in this project creates space for understanding and possibility within the unknown. These possibilities include the mapping out of future collaborative and generative approaches for me to imagine existing in unceded First Nation’s lands as a migrant settler.

The echo as a locative device is not an impossible task, either metaphorically or scientifically. Whales communicate via echolocation within the depths of the waters on Earth and very recently, in 2014, the Rosetta space probe (figure 1) mapped the surface of Comet 67P/Churyomov-Gerasimenko via sound signals. This process worked by measuring the distance a sound signal took to return to the probe, in the way of an echo. This example does not merely present the echo as a way to measure and imagine the shape of a far-away object. If I am to take it back to a metaphor, the echo when looked at in this way allows for the possibility of imagining ourselves as deeply embedded in an understanding of faraway time that is measured from the present but limitless in its future and its past.

The Western myth of the echo

Your first impulse may be to locate this enquiry into the echo within the Mediterranean myth of Echo. The nymph Echo is punished after her talking distracts the goddess Hera from being able to concentrate on spying on Zeus, her husband, as he seduces a woman. Echo is thereby banished by Hera to live in a cave in the mountains and condemned not to speak a word unless her utterance is the repetition of the very last word in a sentence spoken by her interlocutor, in perpetuity. When Echo falls in love with Narcissus, who was too self-obsessed and in love with his own image as reflected on the surface of the water, to pay attention to Echo’s afflicted declarations of love, we see the fullest expression of this cruel punishment.

I am writing this from within the Western institution, so I would be remiss to discuss the echo and not mention this myth. It has after all continued to be an important part of the imaginary of a whole civilisation. As I workshopped possible ways through which to shape my engagement with such an important myth, two options came to the fore:

1. I—a marginalised voice as a migrant settler of the Salvadoran diaspora—could take the character of Echo and rewrite the story to redeem her. However my voice as an artist is a complex one which seeks to remove itself from narratives around victimhood.

2. I could take on the heroic role of rescuing Echo by helping her find the ability to speak her own thoughts, articulating sentences from beginning to end, that she could speak to the distracted Narcissus.

As I contemplated my task, I realised that just as the words that Echo must use are the words of others, the words I would be ‘echoing’ would not be my own but, rather, those of the dominant, visually-focussed Narcissus himself.M. Bull, The Routledge Companion to Sound Studies (Routledge, 2018).277. My own echo would re-piece the words, reconfiguring them from the fragments she repeats.Ibid. That is, I would be overlaying a narrative counterintuitive to the motivations behind this project. But this is counterintuitive not just because it is a Western narrative. The most significant problem here is that the echo, the sound effect itself, is seen as a negative attribute, a type of penance, a limiting shackle which, within this artistic project, it is not. By contrast, the echo in this project is a space of possibility. And while I have rejected the Western myth of Echo as a way to contextualise this practice within the academic context for the above-mentioned reasons, the cave itself is still a compelling part of the myth to me.

Beach cave

When I was a child in El Salvador, perhaps seven years old, I walked away from my family while we were enjoying an outing at the beach. I walked far away and found myself at the front of a cave. It was dark and intriguing. I entered it and walked in on what must have been hundreds of sleeping bats hanging from the rocky ceiling. I screamed out loud, a high-pitched child’s scream that returned to me as an echoic force which triggered the bats into frantic screeching. Inside the cavernous space, hundreds of wings were flapping together in alarm. I ran straight back to my family in a panic, leaving behind the chaotic and frightening cave, with its infinite darkness echoing in echo. I tell this terrifying and exploratory childhood story because the uncertainty, the unknowingness, that I felt in the cave is what floods the sensorial body when the echo is used in music such as dub.Dub music is a genre of music originated in Jamaica characterised by its use of electronic equipment and echo as an effect as part of its intrumentation.

Osbourne Ruddock, otherwise known as King Tubby, pioneered the dub style through the literal ‘overdubbing’Overdubbing (also known as layering) is a technique used in audio recording where a passage (typically musical) has been pre-recorded, and then during replay another part is recorded to go along with the original. The overdub process can be repeated multiple times. of recording tape, which gave the genre its name. The production process entailed one song overlayed onto another, creating a ‘ghost’ of another voice or melody. Hence dub production has a formal quality, evoking layers of cultural memory and timelines through this sonic palimpsest. Artist, writer and sound scholar Louis Chude-Sokei speaks of cultural memory as neither innate or nostalgic but, rather, as an invocation. Within the language of dub, the producer takes on the role of the conjurer, the one asked to assume their role in the continuum of something booming, alive. It is not melancholia—on the contrary, it is a generative space and a place of acknowledgement, a conflation of timelines.

There are many types of effects units, both analogue and digital, designed to distort music to create the effect of the echo, and there are mathematical equations that allow for different types of echoes to be achieved via machine. Boxes with springs inside create a delay effect when applied to a segment of a song, evoking distance and playing with time in such a way as to invocate other temporalities and deeper spaces. In dub, the echo is a holistic device, as described by ethnomusicologist Michael Veal:

In the sonic culture of humans, the sensation of echo is closely associated with the cognitive function of memory and the evocation of the chronological past; at the same time, it can also evoke the vastness of outer space and hence (by association), the chronological future. Most obviously, dub is about memory in the immediate sense that it is a remix, a refashioned version of an already familiar pop song; as such, it derives much of its musical and commercial power from its manipulation of the listener’s prior experience of a song.Michael E. Veal, Dub : Soundscapes and Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae (Middletown, Connecticut : Wesleyan University Press, 2007).

Veal’s conceptualisation of the echo as speaking to chronologies is important to this research, which positions the echo as existing within a circular timeline. Which is to say, the sonically experienced ‘decay’ in the echo is not the ‘end’ of a signal connection, but instead a connection to a source that propagates and returns again and again in rhythm, even if as it fades.

In dub music, the function of the echo is also as a sonic relational device. In his highly reproduced text Dr Satan’s Echo Chamber, Chude-Sokei describes the echo as it functions specifically within the music of the African Diaspora:

This music has helped us ground ourselves in communally created myths that sustain us in the protracted experience of dispersal. After all, Diaspora also means distance and the echo is also the product and signifier of space.Chude-Sokei, Dr Satan's Echo Chamber, 47.

The echo in dub begins with a signal, an element from a familiar song, an instrumental element or a lyric. An effect will then intercept this sound, distorting, enhancing and abstracting it via machines such as an analogue echo, spring reverb units or a digital device. This effected sound is further amplified, played out of a large sound-system tuned to the nuance of the echo.

In the dialogues around dub music—especially for Chude-Sokei, Veal and theorist and filmmaker Julian Henriques—the echo is referred to as a metaphor that abstracts and diffracts a sound of origin, in turn speaking to the dispersal of peoples from Africa across the Transatlantic Ocean because of the way in which the effect itself operates. This view guides this research, privileging sound as an important part of aural traditions and their narratives. For Chude-Sokei, “the echo trailing into infinity can only be the experience of life, the source of narrative and a pattern for history.”Ibid.

Following Chude-Sokei’s remarks on the echo as “the source of narrative,” it is important to ask how narratives occur within sounds, rather than in lyrics and words. Julian Henriques describes the echo as behaving as a verb, a doing in the world, a becoming.J. Henriques, Sonic Bodies: Reggae Sound Systems, Performance Techniques, and Ways of Knowing (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011).165. Henriques draws a poetic parallel between the sonic occurrence of the echo and its use as a metaphor when he speaks to the way in which it behaves within a space. Musically, in dubbing, this is often a reverberating echo gradually diminishing into silence, either coming or going, in the repetition it becomes different.Ibid. It is here that the idea of the echo as a functioning metaphor really comes into play. For the diasporic individual, it is no longer the ‘sound’ of origin but instead a reverberation of it, becoming different and yet still maintaining conversation and connection via repetition with the signal from which it diffracts.

Writer, theorist and filmmaker Kodwo Eshun, likens the echo’s affect to the act of creating a space—chambers able to be navigated or routes through a network of volumes, doorways and tunnels, connecting spatial architectures as refractions bouncing back from any surface create new immersive spaces out of physical walls.K. Eshun, More Brilliant Than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction (Quartet Books, 1998). 65 This space that Eshun speaks of, this collective and subjective space, is alive with a politic that is complex and ancestral, that relates to past and future human experience. The echo in this instance behaves as a connector for experiences and narratives.

Grounding the echo—the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl Kukulkan

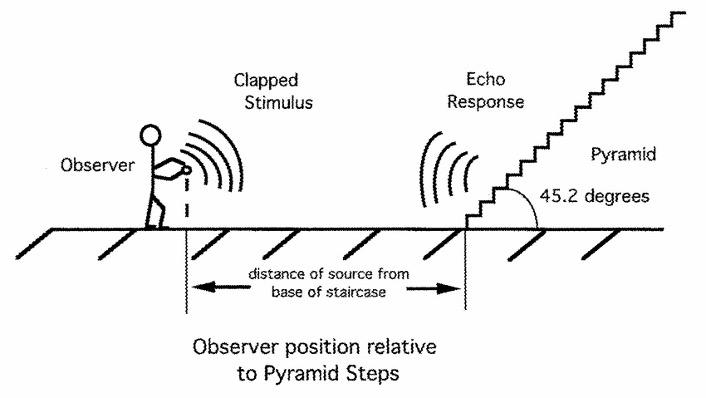

Archaeoacoustics is a branch of research into the acoustics of archaeological sites and artifacts. Archaeoacousticians such as David LubmanNico F. Declercq et al., “A Theoretical Study of Special Acoustic Effects Caused by the Staircase of the El Castillo Pyramid at the Maya Ruins of Chichen-Itza in Mexico,” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 116, no. 6 (2004), http://dx.doi.org/10.1121/1.1764833. 3328. have spent a considerable amount of time researching the physics behind the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl Kukulkan (figures 3 and 4). It is one of many structures on the Chichen Itza Mayan Yucatán peninsula of Mexico, a significant pre-Columbian site dated from 600AD to 1200AD. The Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl Kukulkan is known for recreating the chirping sound of the quetzal bird (figure 2), which occurs when a person positions themselves at the bottom of the pyramid and claps their hands, thus activating the Bragg reflection effect.In very simple terms, the Bragg reflection effect is one whereby sound waves hit and ricochet off surfaces to then diffract from these surfaces, thereby creating a doubling of the initial sound as it bounces out. The length and pitch of the echo also depends on the length the wave travels. This is the sonic effect created when the sound of a clap bounces upwards from one step to another, to arrive at the top chamber. Upon its arrival to the top chamber of the pyramid, the clapping sound is transformed to mimic the chirping of the quetzal, a sacred bird of significance in Mesoamerican culture.

Figure 2. National Geographic, quetzal bird“Costa Rica: In search of the quetzal,” National Geographic, https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/travel/2018/08/costa-rica-search-quetzal.accessed February 8, 2021.

According to archaeoacoustic research, the pyramid’s structure was intentionally built with these sonic qualities in mind. There is also research that suggests that an extra effect was employed to create the chirping sound further asserting that the sonic effect of the pyramid was intentional. Frans A. Bilsen, "Acoustics at Chichen Itza," in Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, ed. Helaine Selin (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2016).1.

Imagine, reader, as I have many times, approaching the bottom step of the tall pyramid, putting your hands together and hearing the familiar sound of your own clapping hands. Via your interaction with and positioning within the space, your relationship with the building, this sounds then returns as the chirping of the very species of bird that the pyramid is named after.

The initial signal in this case, if we are to follow the understandings of the echo already discussed, is not the clapper, but it is instead the chirp of the quetzal. The body becomes a conduit here, as in dub, one that receives and sends out signals in order to connect or, in visual terms, perform a type of retracing.

The echo of the Pyramid of Queztacoatl Kukulkan is important for the development of generative ideas within this project as it provides a critical understanding of the ways in which sound physically instigates a connection to an original signal—one that does not necessarily directly involve contemporary machine space, as in dub, but is a sonic functionality guiding the architectural beyond the visually aesthetic domain.Chude-Sokei. Dr Satan's Echo Chamber, 50.

Figure 3. Temple of Kukulkan at Chichen Itza, Mexico. Photo shows one of its four 91- step staircases .David Lubman, “Convolution-Scattering Model for Staircase Echoes at the Temple of Kukulkan,” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 123(5) (2008), https://asa.scitation.org/doi/10.1121/1.2934779. Accessed 10/08/2019

Figure 4. Key physical elements of the chirped echo system reduced to two-dimensionsibid.

Beyond the fantastic unexpected effect that it creates, the echo at this important Mayan construction at the site of Chichen Itza forms a significant link between timelines. It creates an effect in which the person at the bottom of the steps is connecting, activating and becoming the instigator in a set of cultural, environmental, sonic and architectural relations and communications, even if only for the duration of the echo.

The echo speaks of a set of beliefs about those who built the pyramid and their relationship to the environment— The honouring of the Quetzal is also story-telling about the relational.

Glissant’s description of the ‘relational’ is a way of understanding events and spaces, incidental or intentional, as connections rather than binaries of opposition. Relationality in Glissant’s writing becomes about complex and irreducible wholeness. In the pyramid example that I have presented, the human, the animal, the architectural and the environmental become part of a relational confluence, a story in circularity.

We shall dance by the light of the moon.

My work We shall dance by the light of the moon is a 20-minute autobiographical sound work that I produced in early 2019. It was inspired by a conversation with a friend in which I was encouraged to find out more about the Indigenous people of the region of Morazán, El Salvador, where my mother was born and where I spent a considerable amount of time as a child.

My friend, at his house and me at mine both looked as he sent me links. The obvious way to begin this search was to open the Google search engine on my laptop. The aerial views in the digital realm, as I walked my cursor through the streets, bore no depth. The searches led me to videos on YouTube, and I navigated away from new-age Mayan-themed videos, I found a video of phrases in Lenca/Putum (the Indigenous language of the Lenca people of Honduras and part of El Salvador) translated into English with the Anglo/European linguist’s voice providing a second layer of mediation. The phrases and their translations became the basis for a sound collaboration with my then twelve-year-old son. We studied their pronunciation and chose phrases which were interesting to us, being careful not to create too much of a narrative. The more I searched and read the more this quest became about failure and I found this the most interesting part of the interaction.

The opportunity came along about making a work that referenced this experience. As a mother I am invested in some ways in migrant motherhood and what the passing-down of knowledge could mean in the context of the Salvadoran diaspora. For this work my son and I took turns speaking the words in Lenca and repeating them in their English translation. I titled it "We shall dance by the light of the moon" (sound below).

Listed below are some selected phrases and their translations. The subjects of the phrases are wide ranging. They speak of everyday activities and beliefs or are quite factual. Some , also describe the condition of Lenca/Putum language itself. These phrases were collected by linguist Alan King and presented in a video titled “Useful Phrases in Lenca”:Lepa Productions, “Useful Phrases in Lenca,” YouTube, accessed November 10, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-fAM79o0h34.

| Child | Mother |

| Ma sap inkoloka! | Open your eyes! |

| Remember! | I ep shika! |

| Anum pokampa. | There it comes. |

| Here we eat fresh fish from the ocean. | Nanum sai-shok’in romanpi. |

| Nanum yampi. | Here we are. |

| Here I am. | Nanum yanu. |

| Nanum tulau. | I was born here. |

| Give me your hand! | Koshaka u mika ma! |

| Kasa aya. | Say something. |

| Language enters from the ear. | Putun-na Pi Tokoro-K’ati. |

| Aptakanpa tete-na koko-na putum sharikin kelipa | The elders do not speak Lenca |

| K’ulananka putum shakinikanpa | No one speaks Lenca |

| Kuyakami u lanke-wewe. | No one speaks Lenca |

| Mam roma | eat shit |

| Kisha Ayampi | How do we say? |

| We will dance to the light of the moon | Letz’a i wesh-ti uli kokanpi |

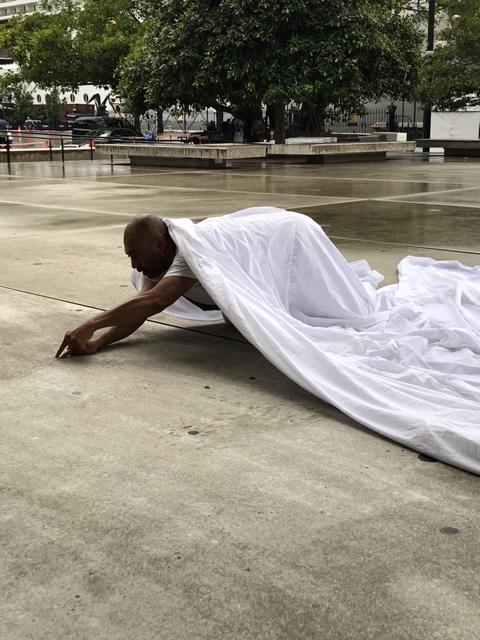

Figure 5. Lucreccia Quintanilla, Our voices together bouncing off these walls, 2019, fabric, string and sound work

This sound work has had a couple of manifestations, however I will speak to the work shown as part of the exhibition m_othering the perceptual ars poetica (2019), curated by Abbra Kotlarczyk and shown in Melbourne at Counihan Gallery. The sound recording of the phrases was housed in a structure sewn by hand and made out of cloth that mimicked the structure of both a cave and a tent (figure 5). Like an echo in a makeshift and precarious cave, the phrases bounced from child to mother and back again.

Just like the structure of this cave was temporal and playful, the exchange was also temporal, a mere attempt. My son and I do not practice Lenca culture, and my grandparents or their grandparents did not speak the language, which is not to say that our ways of life have not been infused with this culture, its humour and its subtle ways of understanding the world. But ultimately, all we had to exchange were these words, as we bounced them off each other and giggled or commented as we recorded ourselves.

Unlike Echo in the Mediterrean myth, the utterings of my son and I of Lenca/Putum words allow us to attempt to understand. But like Echo, this understanding is not close enough to allow us to converse ‘back’ or with ease. Our engagement is removed, but rather than silencing our subjectivity as we repeat the words, we bring to life the incommensurability of our layered cultural positioning, away from the need for clarity or to fit into a binary. This, I believe, is a political position. After all, the art world relies heavily on easy-to-digest, essentialised ‘brands’ reliant on stereotypes of exotic identities. Through this work, I wanted to engage with a particular cultural condition as it exists—unresolved and non-performative—subverting familiar anthropological/museological tropes, mis-readings and misrepresentations, which are all commonplace within institutional frameworks.

Diffraction

In Dub sound, one can hear a distorted beat firing into space. Repetition allows it to come back solid only to be ‘sent away’ again through the echo that is added at the end of each phrase. The Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl- Kukulkan research has led to an understanding of the physics of diffraction, which creates an echo. Feminist theorist Karen Barad’s writing on diffraction speaks of the action of the echo as one of creation:

I want to begin by re-turning—not by returning as in reflecting on or going back to a past that was, but re-turning as in turning it over and over again—iteratively intra-acting, re-diffracting, diffracting anew, in the making of new temporalities (spacetimematterings), new diffraction patterns.Karen Barad, "Diffracting Diffraction: Cutting Together-Apart," Parallax 20, no. 3 (2014/07/03 2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2014.927623.168.

New utterings are made with each diffraction, new temporalities in which each moment is an infinite multiplicity.Ibid., 169. It creates a complex interweaving of utterings and iterations, much in the same way as echo works within dub music.

As Veal describes it, the fetishisation of and reliance on reverberation and delay to create an echo is certainly one of the most pronounced stylistic traits of dub music.Veal, Dub, 2007. An analogue reverb machine, historically used by dub producers, usually comprises a steel box with a coil or two inside it. As the signal is put through and sound enters the box, the springs distort and reverberate. This reverberation is then amplified. As this machine affects a sound signal, what transpires in this space has implications for those in the diaspora as it presents an identification with multiple possibilities and temporalities. It is not a singular homogenised articulation but many, across space and time:

In the sonic culture of humans, the sensation of echo is closely associated with the cognitive function of memory and the evocation of the chronological past; at the same time, it can also evoke the vastness of outer space and hence (by association), the chronological future.Ibid., 198.

A Steady Backbeat

Figure 6. Lucreccia Quintanilla, A Steady Backbeat, 2017, , clay, iPhone playing out a composition by the artist 2017, TCB, Naarm Melbourne. Photo: Cristo Crocker

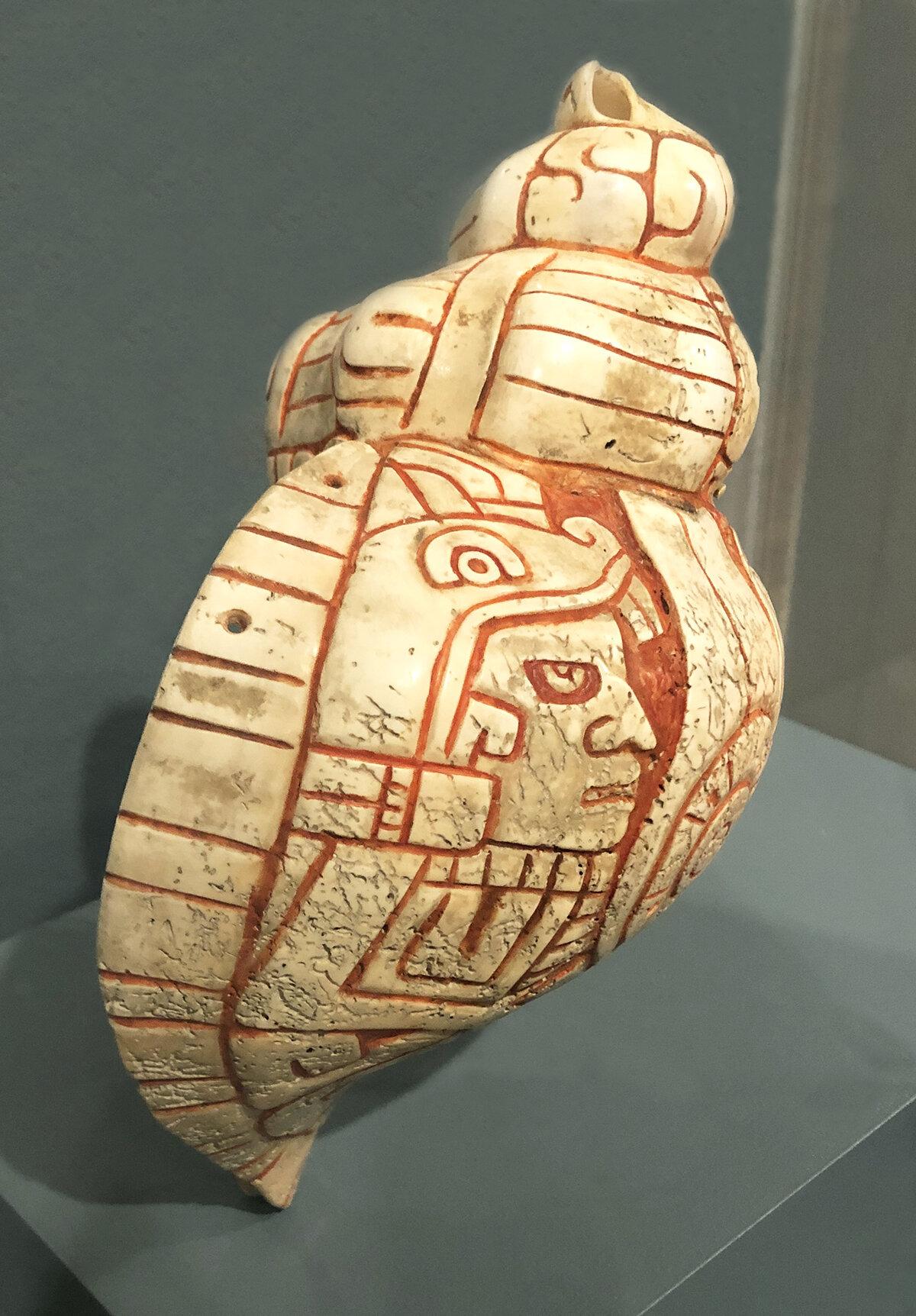

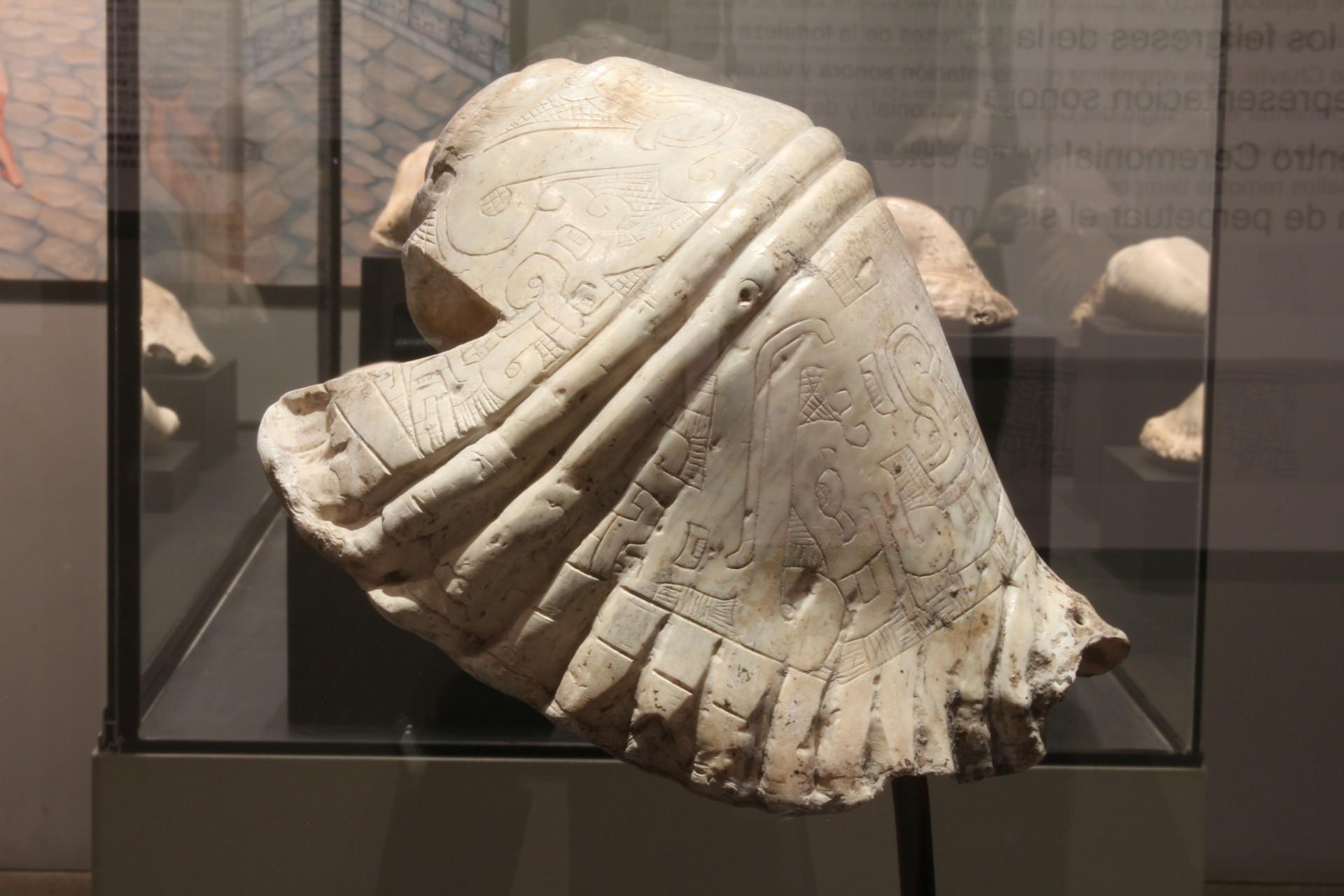

It is with the above understanding of the echo as a mode of conversation that this research project delved into the making of sound, utilising the echo as a device in compositions and their presentation, such as in the series titled A Steady Backbeat (figures 6 and 11). A Steady Backbeat is a series of ceramic works fashioned after the shape of the conch shell, taking advantage of its internal spiral architecture, which I replicated out of clay, for its capabilities as a sonic implement. These ceramic conches amplified looped sound works comprised of compositions of sampled sounds and field recordings. This shape was also inspired by the Mesoamerican ceramic conches I would look at as a child at museums in El Salvador, and later in New York. Conches are used by many First Nations cultures, both in Mesoamerica, and elsewhere, as wind instruments, both in their original form found by the sea as well as in reproductions, which are often tuned by the use of holes drilled in parts of the shell (figure 8 and 9).

Figure 7. Lucreccia Quintanilla, If you close your eyes you will see what is really there from the A Steady Backbeat series, 2017, flowering introduced species weeds collected from Merri Creek (Naarm, Melbourne), clay, iPhone playing out a composition by the artist. Exhibited at Everything Spring, 2017, The Honeymoon Suite Gallery, Narrm Melbourne. Photo: André Piguet

Figure 8. Unknown Mixtec artist (Mexico), Carved Conch Shell Horn, 1300CE, conch shell carved with motif of a human dressed in a helmet. Denver Art Museum Collection, gift of Mr and Mrs Morris A. Long“Rhythym and Ritual,” DARIA, accessed February 8, 2021, https://www.dariamag.com/home/rhythm-and-ritual.

Figure 9. Unknown Colima artist (Mexico), Conch shell trumpet effigy, clay, 300 BCE to 200 CE. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. https://art.thewalters.org/detail/80266/conch-shell-trumpet-effigy/ accessed 5/2/2021

The conch works I created were the result of a residency in Banff, Canada. As I settled into my studio for a month there, I wrote the following down on a piece of paper after a conversation with my son, who came with me. I wrote it after thinking about how relatively close to my family in El Salvador I was and contemplating that, even though I could not go there at that time, I was looking at the same night sky:

When I was a child, I believed stars were tiny windows into light. Like a mantle, the night was pierced to let the light on the other side come through.

A couple of days later I borrowed The Parable of the Sower (1993) by Afro-futurist writer Octavia E. Butler from the library and on page five I found myself reading the following:

When I was your age my mother told me that the stars—the few stars we could see— were windows into heaven. Windows for God to look through to keep an eye on us.Octavia.E. Butler, Parable of the Sower (Open Road Media Sci-Fi & Fantasy, 1993).5.

These words were said by Corazón, the stepmother of the central character in Butler’s story, who, like me, has Latin American ancestry. In Mayan cosmology, the stars are referred to as the ‘eyes of the night’, although without the judgement added much later by the colonial Catholic layer, where one is watched by God.

With this coincidence in mind, I worked on experiments with field recordings of walks I took around the Rocky Mountains, to engage with the surroundings. I may not have been able to convey the sky, which after all is not audible (at least with the equipment I had access to), but what is audible in these pieces is the sound of the movement of creaking trees and their leaves. To make reference to the comforting company this analogy of the sky provided my work, I created a short looping sound composition comprised of drum beats, much like a heartbeat (in place of the sound of the ocean, which is the sound most commonly associated with the placing of the ear near the conch opening). These sounds pieces are played continuously throughout the time the works comprising A Steady Backbeat are shown. The sound works are played out of broken mobile phones which are still able to function as music players and can be placed with the phone’s speakers inside the conch in order for the sound to be amplified. Using the broken phones was a crucial choice as it eliminated the use of high-end or complex external sound equipment, thereby placing emphasis on the casual and the failed everyday contemporary object being repurposed (figure 11).

Anthropologist Stefan Helmreich wrote a detailed essay titled “Seashell Sound” Echoing Ocean, Vibrating Air, Brute Blood” in which he describes popular perceptions of the conch and its sound in European lore and literature. Helmreich describes the theory that what we hear when we place our ear to a conch is the sound of our own blood flowing through our ear canal. There is also another theory on the conch that believes that trapped human spirits is what we hear sounding through the intricate internal structure within the seashell.Stefan Helmreich, "Seashell Sound: Echoing Ocean, Vibrating Air, Brute Blood," Cabinet Magazine Winter 2012-2013, 48 (2013), accessed 5/7/2016, https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/48/helmreich.php.

Most relevant to this project, however, is Helmreich’s writing on the way “in which shells concentrate memory by gathering the history of the vibrating world around them.”Ibid. The echo that is heard via the conch shell is theorised by Helmreich as a transmission of both the individual and collective experience. As he elaborates:

We have the meeting of two models for seashell sound: a mythic model that has seashells as channels for voices from a communal past, and a materialist model that has seashells as resonant chambers of individual, located experience.Ibid.

Within the context of this research project, the conch works are made to offer intimate listening experiences. That is, to listen to the sound within the conch one has to bend down close as they are floor-based works supported by small patches of sand that serve as support and speak to their origins as ocean and animal. On one occasion, the works were shown surrounded by invasive foreign species (which stop the growth of native plant species), which I uprooted from the banks of the Merri Creek (figure 10). My daily commute from home to studio incorporated a walk alongside the creek, which is where I first noticed these flowering plants during spring. I had noticed that these plants were being sprayed by local council workers and did further research. The weeds continued to flower and dry throughout the duration of the exhibition. It was important that these conch works were responsive to the surrounding place and conditions of where they were shown.

After completing the above works I began to research the conch shells which had inspired them and which I had seen at museums as a child. I wanted to find out the context in which they were used as instruments. Whilst conversing about this with a Chilean friend I found out about their uses in Perú by pre-Incan peoples who also used the conch shells locally known as a “pututus” as instruments (figure 12). The Chavín de Huántar structure in the Andes is a site built in 1200 BCE and is made up of many chambers which have the ritual function of amplifying the acoustic dynamics of the pututu as an instruments specifically the low frequency sounds – the bass sounds that are felt through the body –Archeoachoustics researcher Miriam A. Kolar has written widely about what she has identified in the Chavín de Huántar a construction specifically built to function as a resonant place to play the pututu in an amplifying, flow directing ritual-space.Miriam A. Kolar, "Chavín De Huántar Archaeological Acoustics Project," accessed 20/02/2021. https://ccrma.stanford.edu/groups/chavin/project.html.

It is here where the conch in the most intimate based aspect of this research overlaps with an understanding of sound frequencies and intersubjective collective understanding in event based work.

Figure 10. Lucreccia Quintanilla, If you close your eyes you will see what is really there from the A Steady Backbeat series, 2017, flowering introduced species weeds collected from Merri Creek (Narrm, Melbourne), clay, iPhone playing out a composition by the artist. Exhibited at Everything Spring, 2017, The Honeymoon Suite Gallery, Narrm Melbourne. Photo: André Piguet

Figure 11. Lucreccia Quintanilla, A Steady Backbeat, 2017, , clay, iPhone playing out a composition by the artist 2017, TCB, Naarm Melbourne. Photo: Cristo Crocker

Figure 12. Unknown Andean artist (Peru), Chavin Pututus, 3,000 year old conch shell horn, conch shell carved with motif. National Museum in Chavín de Huántar, Photos by José Luis Cruzado.“Uncanny Acoustics: Phantom Instrument Guides at Ancient Chavín de Huántar, Peru” Miriam A. Kolar, https://ccrma.stanford.edu/groups/chavin/ASA2014.html accessed 20/02/2020

Ritual

Figure 13. Lucreccia Quintanilla, General Feelings Soundsystem, as part of the Barrio//Baryo collaboration with Carolina Garcia, 2017, Brunswick Mechanics Institute, Naarm Melbourne. Photo: Laura Du Ve

The most important aspect of the soundsystem, much like the chambers of Chavín de Huántar lies in its focus on the experience of bass frequencies. While engaging in intimate contexts, this research also identifies the importance of sound in a collective scale of engagement and addresses this need by creating the conditions for the relational via sound amplification and affect. My soundsystem General Feelings Soundsystem (figure 10) is a 2 x 1.5m speaker stack built in the style of Jamaican soundsystems.A speaker stack working on the mono rather than stereo format whereby the frequencies—high, medium and low—are separated, with a special focus on the bass (low) frequencies which are felt through the body rather than heard. This soundsystem is a large part of an ongoing engagement with sound, which has been in operation since 2014 and is the first female built soundsystem in Australia. The soundsystem works on the premise of the traditional speaker stack used to play dub, reggaeReggae music is a popular music that developed in Jamaica in the 1960’s. From a confluence of sounds itself. It is a slow tempo music. Reggae has come to be influential to many others styles and over time has travelled and adapted beyond the Caribbean. and dancehall Dancehall music developed from reggae and other musics in Jamaica in the 1970’s. Dancehall music is a more exuberant in comparison to reggae and was developed through a DJ scene and with a more digital instrumentation.

music in the soundsystem culture that developed in Jamaica. This culture has travelled around the world, thriving in the UK and in Latin America, most notably as picòs in Colombia.The history of the picò and its transcultural genealogy has been written about in detail by anthropologist Deborah Pacini Hernandez. See: Deborah Pacini Hernandez, "Auto Italia, Published, Pico: Sound Systems, World Beat and Diasporan Identity in Cartagena, Colombia," Auto Italia, accessed 2020. https://autoitaliasoutheast.org/published/pico-sound-systems-world-beat-and-diasporan-identity-in-cartagena-colombia/.. On a practical level, my role as a soundsystem operator has meant that I have learnt the complex physics and electronics of operating various amplifiers and speakers. How the speakers behave, and how they sound in different contexts according to the forms and acoustics of surrounding architecture, is tested and my knowledge expanded every time the speakers are used.

General Feelings Soundsystem (figure 13), rather than functioning within the parameters of one particular sound, has adaptability at its core and this is displayed in the way it travels to different communities and contexts and plays different sounds, sometimes experimental sometimes more conventional and musical. The soundsystem is perceptive and careful, and while not auditorily or physically discrete, its approach is responsive to the needs of a community in the time it works for them. This method of working is similar to what feminist architect Céline Condorelli terms as “structures of support.” For Condorelli the building of these structures of support begins from an intuition that amplifies potential in form, which in this project is the ‘vibe’ or space created through which the collective may be able to sound/hear/feel

the unspoken, the unsatisfied, the late and the latent, the in-process, the pre- though, the not-yet manifest, the undeveloped, the unrecognised the delayed the unanswered, the unavailable, the not-deliverable, the discarded, the over-looked the neglected the hidden, the forgotten, the un-named … the missing, the longing, the invisible the un seen, the behind the-scene, the disappeared, the concealed, the unwanted, the dormant.C. Condorelli, G. Wade, and J. Langdon, Support Structures (Sternberg Press, 2009).16.

Writing in 1980, writer, curator and feminist/socialist-activist Lucy Lippard described a set of responsive models of interaction, a type of value system that insists upon cultural workers supporting and responding to their constituencies. These three models of interaction are:

Group and/or public ritual.

Public consciousness raising and interaction through images, environments and performances.

Cooperative, collaborative/collective or anonymous art making.(sn:43)

While these are now very much of their time, in that activism has adapted to political and other conditions such as the internet, Lippard’s three models are all characterised by an element of outreach—a need for connection beyond process or product—and an element of inclusiveness which also takes the form of responsiveness and responsibility for one’s own ideas and images. In other words, the outward and inward facts of the same impulse.

There are some soundsystem events, such as Barrio//Baryo, where I get to have more of an active role in creating space. This event was a collaboration with artist Caroline Garcia and together we curated works by different artists in Naarm Melbourne, towards a final performance event that spanned an entire afternoon and evening. This time slot allowed for a wide breadth of ages to be able to attend—children, parents and grandparents—creating a multigenerational space. To this end, there were performances from Lit Queens, a rap group of young girls, as well as a dance performance by KStar Studios with children aged from eleven to fourteen years old. Artist James Nguyen (figure 14) and his aunt presented a playful performance piece together, which involved the wearing of matching elaborate headdresses as well as incorporating physical and spoken multi-language play, making reference to internet communication and cross generational family relationships. With the thought that there would be children in attendance I decided to create a visual/sculptural ode to the soundsystem by making a large piñata to resemble the colours of the General Feelings Soundsystem for the kids to smash (figure 15).

Figure 14 . Telstra – OTBOT, James Nguyen,Thị Kim Nhung, Nguyen Công Aí, 2017, Brunswick Mechanics Institute, Narrm Melbourne. Photo: Laura Du Ve

Figure 15. Lucreccia Quintanilla, General Feelings Soundsystem, as part of the Barrio//Baryo collaboration with Carolina Garcia, 2017, Brunswick Mechanics Institute, Narrm Melbourne. Photo: Laura Du Ve

Live sound works were commissioned from Chilean artist and ongoing collaborator Bryan Phillips (Galambo) as well as from Raquel Solier (Various Asses) and Neil Cabatingan (Yumgod) (sound above), who created collaborative works. Phillips worked with the sounds of Chilean First Nations folk music and its progression into a type of dub cumbiasCumbia is a genre of music that is played all throughout the Americas. It is a combination of African and indigenous rhythms., as deeply experimental tracks in their articulation. In the case of Solier and Cabatingan, they created tracks crafted from vinyl brought over from the Philippines by Solier’s grandparents decades earlier, vinyls long forgotten and left in an old box. As they were shaped via sampling and other production techniques, these old songs became new. These new tracks in turn become a contemporary way of ‘grounding’, via the layering that takes place—using melodies, drums and other aspects needed for musical arrangements—in the construction of contemporary dance music.

The soundsystem work as well as other aspects of the project were focussed on the amplification of these moments of speaking to, and engaging with, narratives, and their occurrence via sound. This is an ongoing transcultural and relationally-based project, one that is curated and detailed within the oeuvre of the aesthetics of celebration, experimentation and, most radically, joy. The soundsystem, as the amplifier taking up space, engages in an action of sounding, presence, presentation and expression.Henriques.248. This is in contrast to the model of representation of difference within an otherwise mostly Western artistic context or a space of contemplation, examination or objectification of the cultural practice of black, brown and queer bodies who were present at the Barrio//Baryo event. This event as well as others involving the soundsystem work within the sociocultural parametres of the music-led event.

Henriques has developed an understanding of sound and the ‘experiential’ by

… [t]riangulating the Sonic Logos claims that thinking through sound encourages the kind of sensibility that might prove useful for understanding the ways of knowing to be found in other situations and settings.Ibid., 248.

Henriques work around the sonic logos has been a highly significant influence in this research. Henriques puts forth the case that the sonic logos, by which he means logic—sociocultural based rhetorical understanding of sound—and pathos—a sensorial, emotional form of affect in sound experience—work together relationally with ethos—the contextual world around the collective.Ibid., 265. Thus, the soundsystem in the context of the event is able, according to Henriques, to make complex connections that weave the intimate and the collective experiences together.

Activist, artist and writer Fjorn Butler describes the source of the sound, the speakers themselves, as engaging in a collaborative echoic effect:

As a sound system simultaneously absorbs while it outputs, rogue frequencies are not just a contingency but a property. A sound system’s signal can inevitably project beyond the intended parameters of its meaning, resonating and accumulating multiple significances, intersecting worlds and thus placing pressure on the points at which structures are joined at points of difference. Further, the escalation of a signal into feedback and sustained resonance does not nullify its source, but beckons it. Thus, an echo is not a sign of static individuation or a property that can be grasped and possessed. Receiving, listening, sensing, emitting are complex and shared experiences—a collaboration.Fjorn Butler, "Records of Displacement and the Echo as a Beckoning Artifact," (2019), accessed 5/12/2020, https://disclaimer.org

Taking Butler’s relational understanding further, Henriques describes the relationship between the body and the echo as:

Bodies relating taking turns between ebb and flow … contraction and dilation, growth and decay, condensation and rarefaction, contraction and relaxation, inhalation and exhalation.Julian Henriques, Milla Tiainen and Pasi Väliaho, "Rhythm Returns: Movement and Cultural Theory," Body & Society 20, no. 3-4, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1357034X14547393.

The soundsystem event is also one of celebration of a collective experience of the sensorial and it often presides over a type of ritual much like the one Lippard described earlier. A structure through which communities come together and experience both a collective and individual sense of relation to themselves and the larger narrative taking place, to which they are also adding. According to Lippard’s shaping, ritual is not one of

wishful fantasy, of skimming a few alien cultures for an exotic set of images. Useful as they may be as talismans for self-development, these images are only containers. They become ritual in the true sense only when they are filled by a communal impulse that connects the past (the last time we performed this act and the present (the ritual we are performing now) and the future (will we ever perform it again?).Lippard.Sweeping Exchanges, 264.

What Lippard is referring to is a deep engagement with a type of genealogical awareness, such as that which took place in Barrio//Baryo—an unpredictable, irreducible and joyous space, as well as space of experimentation, of futurity and engagement with ancestral spaces in ways that were sometimes explicit and sometimes opaque. This is the time that Lippard is referring to. Time to Lippard provides a deep rather than a superficial engagement via an aesthetic of exotic motifs. An aspect to these events, is the act of hosting, done through catering events with food, employing an MC to introduce the performers; in other words, creating a sense of belonging. Hosting becomes not just a way to accommodate and welcome, but also a way to facilitate an atmosphere through which a narrative can thrive and be experienced as it is being constructed and in turn received in real time. Geologist, artist and researcher on sound and affective politics AM Kanngieser describes the space of sound as generative:

Worlds are made out of these spaces in part through the conversations had within them. The imaginaries that these worlds produce [map] spatial acoustics into a plane of the relational.AM Kanngieser, "A Sonic Geography of Voice: Towards an Affective Politics," Progress in Human Geography 36, no. 3 (2011). Here, Kanngieser refers to their project which involves mapping. Despite this specificity, this way of theorising sound is very relevant to the way sound functions within creative projects.

Writer on sound and Indigeneity in North America Dylan Robinson terms ‘difficult music’ that which is dissonant and analogous and in interaction with difficult social and political issues. Dylan Robinson, Hungry Listening Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies (University of Minnesota Press, 2020).181. By this Robinson doesn’t necessarily mean abrasive sounds, but what he refers to is a sonification that articulates complexity and unpredictability, which eludes being simplified or easy to read. It is through this ‘difficult music’ that contemporary engagements with ancestral ways are formed, ways that can articulate conversations with forces not yet here. Similarly, sociologist Monique Charles identifies Grime music as being part of the ongoing collective narrative of the Black diaspora in the United Kingdom. Charles identifies this music’s politics as residing in its validation of the communities that engage in its making and the materiality of their lived experience of race and class hidden from the dominant narratives of Britishness. Charles argues that whilst Grime does not deal with overt political context, that sounds which tell the narratives of the Black Atlantic diaspora in Britain are political in that they simply voice an experience, in its own terms.M. Charles, 'Hallowed Be Thy Grime?: A Musicological and Sociological Genealogy of Grime Music and Its Relation to Black Atlantic Religious Discourse' (#Hbtg?) (University of Warwick, 2016). 355 The necessity for both these approaches to sound is one that has much relevance to non-white communities living in the Australian context and it is one that focuses on the creation and experience of a complexity rather than on the static politics of identification.

Conclusion

Having the echo as a foundation through which to explore sound making has been very enriching and generative for its functionality within both the intimate and collective realms, with a potential for the complex and the adaptive and the political in the way of Robinson’s ‘difficult music’.